Why is the Female Gaze still such a taboo? Over one hundred years after a female artist first painted a male nude, the male gaze still seems to be regarded as the norm. Time to redress the balance, says life model Del Mikdit.

My top artist hero isn’t a hero but a heroine. It’s the French painter Suzanne Valadon. Famous for her ferocious public bust-ups with both her boyfriend André Utter and her alcoholic son the artist Maurice Utrillo, the three of them were known in the artists’ colony on the Butte Montmartre as the Wicked Trinity.

But that’s not why I love her. It’s because she was the first female artist to paint a full frontal male nude.

she was the first female artist to paint a full frontal male nude.

Arrboa and I visited her former home in Montmartre – now a museum – last year. There’s a wonderful reconstruction of her studio – brushes and paints scattered over her bench, half finished canvases lying around everywhere. It’s almost as if she might wander in at any moment and ask you to pose for her. (Yes please! I’d have my kit off for her in seconds.)

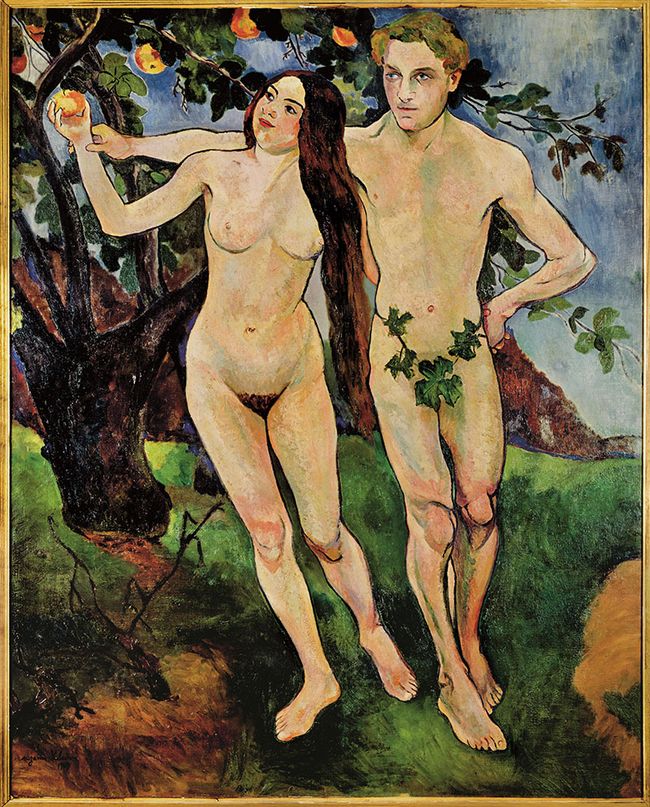

But in her most famous male nude painting – her Adam and Eve of 1909 (posed by herself and her lover Utter, and now held at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris) – she ended up covering Adam with fig leaves. Not because she was scared of penises. Oh no! But because she wanted the work to be accepted at the Salon in 1920 – and they certainly wouldn’t have stood for a penis painted by a woman (although they do seem to have been OK with Valadon showing her own pubic mound).

Fast forward to 2021, and the opening of the refurbished Courtauld Gallery in London.

In the stairwell is a specially commissioned painting by Cecily Brown showing two naked men as its centrepiece. (Catch it while you can; it’s only on display for four years, so its end may be nigh.)

‘In the realm of predominantly male artists gazing at the female nude,’ the Courtauld curators say, ‘she decided to make the male body her central theme.’ Admirable indeed. But why, a century after Valadon’s pioneering work, should this still be an issue?

During my career as a professional life model, I’ve posed for hundreds of sessions, and been gazed upon by probably thousands of artists. And most – although by no means all – have been female. I’m not aware that any female artist who I’ve posed for has ever been driven mad or struck blind at the sight of my naked body. Yet the idea of the male gaze on the female nude as being the norm – not the other way round – remains as powerful as ever.

Take a look at this painting - now part of the Royal Collection Trust. It was done by Johan Zoffany and shows the founder members of the Royal Academy in the early 1770s. But not quite all of them. There were two female Academicians – Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman. But they couldn’t be shown in this painting because there were – gasp! – two male nudes in the room. Goodness knows what damage would have been done to the ladies’ delicate little constitutions if they’d seen them.

Zoom on around 140 years and even Dame Laura Knight – the first British woman artist to paint a female nude (her Self Portrait of 1913, now in the National Portrait Gallery in London) – wasn’t allowed as a student to paint from life, but had to work from casts and drawings.

I’m not sure how much better it’s got since – neither for the artists nor, sadly, for the models.

From time to time, people ask me whether I feel vulnerable when I’m posing naked. And I have to say – no, I don’t, and I never have. Even when a tutor has invited the students to think of my body as a set of geometric shapes – blatant objectification if ever there was – I still feel not vulnerable but liberated, because I’m doing something that most people would never dream of doing.

Many female models, I know, feel the same. There’s one lovely lady whose work I admire who is supremely comfortable in her own skin. ‘It's quite strange living in a body and having thoughts about it, and the more detached seeing it through others’ eyes when they sketch,’ she says.

Then there’s the academic Kate Lister, who revealed in an article in the i newspaper last year that she had posed nude when she was a student and skint. ‘There were no two ways about it,’ she acknowledged the first time she saw the results, ‘The woman in those pictures was beautiful, and she was me.’

And then there’s the model booker for one group I work for who realised that, one year, life drawing day was going to fall on her birthday. So she decided to be the model herself that day – posing nude in front of all her friends. How did you feel about the experience? I asked her. ‘Empowered’ was her reply.

All these stories are inspiring, but I have also encountered female models who have at times felt profoundly uncomfortable under the male gaze and – from what they’ve reported – with good reason. So I suspect that, more often than not, the experience of displaying yourself naked is significantly different for a man.

Here I am with a lovely group of friends at Brixton Life Drawing last year. It was an incredibly enjoyable evening – a great experience for everyone – and I hope that comes across in this picture.

Now… if the model, clad in nothing but a dressing gown, had been female, and she was flanked by a bunch of men all showing off their drawings of her, would you feel differently about the photo? I’m pretty sure many of you would – and you’d probably feel uncomfortable about it too – about the overtones of male power and exploitation that it engendered.

And therein lies the dilemma.

Naked, and subjected to the gaze of a group of people who they may not even know, female models do have to be on their guard, to have a care for their personal safety. Male models, on the other hand, are much more likely to feel flattered at being the centre of attention.

If you’re looking for an answer from me to this dilemma – a way of eliminating the inequity, and the power imbalance that it implies, well – sorry – I haven’t got one. But I do hope I can do something, on my own, in a very small way, to redress the balance.

I actively accept that the artists who draw and paint me (predominantly female, remember) may sometimes regard me as a technical challenge to be overcome, rather than a real person to be sensitively depicted. If they comment on my big nose, my scrawny neck, my pot belly or (now) the large operation scar on my shoulder, I think that’s only fair recompense for the centuries during which men have disregarded the feelings of female models in their quest for the image they desire.

She had her dream job: Looking at naked men all day

A lovely art tutor for whom I model from time to time once told me that she had her dream job: ‘Looking at naked men all day’. It was a joke of course, but occasionally – just occasionally – I do wonder whether, for one or two of the artists who draw me, a life drawing session is an opportunity to gaze on a nice naked man in a completely safe environment. Voyeurism? Possibly – and I accept that too.

Is that because I’m an exhibitionist? No. (Well… maybe just a bit.) But it’s mainly because I desperately want to do what I can to make amends for the centuries of tyranny imposed on females by the male gaze. To make a small contribution to the normalisation of the female gaze on the male nude.

Because, to judge from the experience of Cecily Brown, the creator of that painting in the Courtauld, not much has changed in the hundred years since Suzanne Valadon exhibited her Adam and Eve at the Salon.

Interviewed by the Telegraph in 2021, Brown said it was very frustrating when she painted a male nude and people said it was homoerotic.

‘So, female nudes are for the male gaze?’ she enquired. ‘And then male nudes are also for the male gaze, even when they’re by a straight woman?’

Looks as if we still have a way to go before the female gaze is accepted as legitimate. Let’s start now.